| The Players |

| |

| |

| Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte |

| |

Centuries ahead of her time, Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was a beguiling and unconventional woman who broke all the rules and masterminded an ingenious and perilous conspiracy that scandalously incriminated the rich and famous and may well have paved the way to the guillotine for Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI, ending 800 years of absolute Monarchy. Centuries ahead of her time, Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was a beguiling and unconventional woman who broke all the rules and masterminded an ingenious and perilous conspiracy that scandalously incriminated the rich and famous and may well have paved the way to the guillotine for Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI, ending 800 years of absolute Monarchy.

It all began in the heart of Jeanne de la Valois-Motte, whose motivation was not personal wealth but rather a quest for the return of her family honor. Although she was born into a family directly descended from Henry II, King of France in the 16th century, Jeanne's parents were disenfranchised after falling out of favor with the Royal court. Soon after, young Jeanne was tragically orphaned. Her only inheritance was a tattered genealogical chart proving her noble origins. Thereafter, Jeanne dedicated her life to a single purpose: to regain her heritage and take her rightful place at the Royal Court of Versailles.

First, to gain access to the Royal Court, Jeanne married a dubiously titled Count, Nicolas de la Motte, a philandering husband of convenience. Once within the walls of the great palace, she enlisted the tutelage of a court rogue, Retaux de Villete, who taught her everything he knew about court life and its invidious cast of characters. However, try as she might to gain favor at Court and reinstate her family name, Jeanne was coldly ignored. Her only option was to buy back her honor. To accomplish that, she would need a fortune. So Jeanne came up with a clever and dangerous scheme. Consequences be damned.

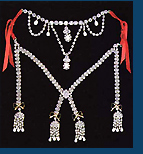

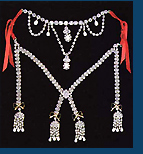

At the center of Jeanne's plan was a spectacular and outrageous piece of jewelry, a 2,800-carat, 647-diamond necklace. It was so costly that no Royal Court in Europe could afford to purchase it. France's royal jewelers had created the elaborate string of diamonds for the mistress of King Louis XV, Madame du Barry. However, before the piece was completed, the King died and his mistress was banished from Court. The jewelers then tried to sell the opulent necklace to Marie Antoinette, but when the Queen flatly refused their masterwork, they faced imminent bankruptcy. Desperate for a sale, they began to look for ways to approach the Queen in a more discreet manner. At the center of Jeanne's plan was a spectacular and outrageous piece of jewelry, a 2,800-carat, 647-diamond necklace. It was so costly that no Royal Court in Europe could afford to purchase it. France's royal jewelers had created the elaborate string of diamonds for the mistress of King Louis XV, Madame du Barry. However, before the piece was completed, the King died and his mistress was banished from Court. The jewelers then tried to sell the opulent necklace to Marie Antoinette, but when the Queen flatly refused their masterwork, they faced imminent bankruptcy. Desperate for a sale, they began to look for ways to approach the Queen in a more discreet manner.

Conveniently, the royal jewelers came to believe that Jeanne was part of the Queen's inner circle and pleaded with her to intercede on their behalf. This happened only after Jeanne had secured a middleman of great wealth: Louis de Rohan, Cardinal of all France and a debaucher of legendary proportions. Rohan desperately desired the Prime Ministership, but his path was consistently blocked by Marie Antoinette, who had come to despise him.

Through forged correspondences, the Comtesse persuaded him that she was very close to the Queen, and would pass letters to her on his behalf enabling him to argued his case with the Queen directly. Eventually, the letters became very warm and suggestive. Rohan was convinced that the Queen loved him, and he became ardently enamored of her.

The Cardinal became insistent about having a face to face meeting with the Queen, to confirm their new communications and possible expression of romantic interests. For this purpose, there was a dramatic meeting planned between the Queen and the Cardinal, for the Queen to make her true feelings known to him. An actress was hired to play the role of the Queen at the meeting, which was held on the poorly lit grounds near le Petit Trianon. The Cardinal was fooled and the conspiracy continued.

The Comtesse further persuaded the Cardinal that Marie Antoinette desired that he secure the money for the luxurious necklace in order to keep the purchase a secret from a public increasingly angered by her excesses. After their moon-lit meeting, Rohan was easily enticed into agreeing to the transaction when Jeanne suggested the Queen might repay him with the coveted position of Prime Minister.

Though Marie Antoinette probably never heard any of this, the jewelers were told that the Queen agreed to their price. Rohan, to endear himself with the Queen, negotiated the purchase. Though Marie Antoinette probably never heard any of this, the jewelers were told that the Queen agreed to their price. Rohan, to endear himself with the Queen, negotiated the purchase.

There were many other twists and turns, lies and forgeries. In the end, the Queen asserted that she had never ordered or received the necklace. The necklace accompanied the Comte de la Motte to London, where he had it broken up in order to sell the stones in England and mainland Europe.

Rohan was denounced. Jeanne de la Motte was arrested, as were various forgers, actors, and courtiers that were thought involved in the affair. A sensational trial resulted where Cardinal Rohan was acquitted and Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was found guilty. The public sympathized with her. She was condemned to prison for life in the Salpêtrière Prison, but soon escaped and made her way to London. She remained in London where she published her memoirs. |

|

| |

|

|

| Cardinal de Louis Rene Edouard Rohan |

| |

Cardinal de Louis Rene Edouard Rohan, the Prince de Rohan-Guemenee and Archbishop of Strassburg, a cadet of the great family of Rohan, which traced its origin to the kings of Brittany and was granted the precedence and rank of a foreign princely family by Louis XIV. He was born in Paris on the Septemeber 25, 1734. Members of the Rohan family had filled the office of Archbishop of Strassburg starting from 1704. It was an office, which made them Princes of the empire and the compeers, rather of the German Prince-Bishops than of the French ecclesiastics. Cardinal de Louis Rene Edouard Rohan, the Prince de Rohan-Guemenee and Archbishop of Strassburg, a cadet of the great family of Rohan, which traced its origin to the kings of Brittany and was granted the precedence and rank of a foreign princely family by Louis XIV. He was born in Paris on the Septemeber 25, 1734. Members of the Rohan family had filled the office of Archbishop of Strassburg starting from 1704. It was an office, which made them Princes of the empire and the compeers, rather of the German Prince-Bishops than of the French ecclesiastics.

Destined from his birth for high office, Louis de Rohan was nominated in 1760 to coadjutor to his uncle, Constantine de Rohan-Rochefort, who then held the archbishopric, and he was also consecrated bishop of Canopus. However, he preferred the elegant life and the gaiety of Paris to his clerical duties and had ambitions to be a figure in politics. He joined the party opposed to the Austrian alliance, which had been cemented by the marriage of the Archduchess Marie Antoinette to the Dauphin. This party was headed by the duc d'Aiguillon, who in 1771 sent him on a special embassy to Vienna to find out what was being done there with regard to the partition of Poland.

Rohan arrived at Vienna in January 1772, and made a great noise with his lavish fetes. But the Empress Maria Theresa was implacably hostile to him; not only did he attempt to thwart her policy, but he spread scandals about her daughter Marie Antoinette and shocked her ideas of propriety by his debauchery and luxury. On the death of Louis XV (1774), Rohan was recalled from Vienna and coldly received in Paris. The influence of his family was too great for him to be neglected. For this reason, he was made Grand Almoner (1777) and Abbot of St Vaast (1778).

In 1778, he was made a Cardinal on the nomination of Stanislaus Ponia-towski, the King of Poland. In the following year, Rohan succeeded his uncle as Archbishop of Strassburg and became Abbot of Noirmoutiers and Chaise-Dieu. His various preferments brought him in an income of two and a half millions of livres. Yet the Cardinal was restless and unhappy until he should be reinstated in favor at court and had appeased the animosity, which Marie Antoinette felt against him. In pursuit of this object he fell into the hands of a gang of intriguers, the Comtesse de la Motte, the notorious Cagliostro and others, whose actions form part of the "Affair of the Diamond Necklace".

Rohan certainly was led to believe that his attentions to the Queen were welcomed, and that his arrangement by which she received the famous necklace was approved. He was the dupe of others. At the trial before the Parliament (1786), his acquittal was received with universal enthusiasm and regarded as a victory over the court and the unpopular Queen. He was deprived, however, of his office as Grand Almoner and was exiled to his Abbey of Chaise-Dieu.

He was soon allowed to return to Strassburg, and his popularity was shown by his election in 1789 to the States General by the clergy of the Bailliages of Haguenau and Weissenburg. He at first declined to sit, but the States General, when it became the National Assembly, insisted on validating his election. However, as a Prince of the church in January 1791, he refused to take the oath to the Constitution, and went to Ettenheim in the German part of his diocese.

In exile, his character improved and he spent what wealth remained to him in providing for the poor clergy of his diocese who had been obliged to leave France. In 1801, he resigned his nominal rank as Archbishop of Strassburg. On the 17th of February 1803, he died at Ettenheim. |

|

| |

|

|

| Jacques Necker |

| |

Jacques Necker, 1732-1804, Director of Finance under Louis XVI. Having gained a reputation as a financial writer, Necker was appointed France's Directory of the Royal Treasury (1776) and a year later Director General of the Finances. In addition to attempting to raise money for the American War of Independence, he instituted a number of financial and social reforms, which earned him the hostility of the aristocracy and even Marie Antoinette. Jacques Necker, 1732-1804, Director of Finance under Louis XVI. Having gained a reputation as a financial writer, Necker was appointed France's Directory of the Royal Treasury (1776) and a year later Director General of the Finances. In addition to attempting to raise money for the American War of Independence, he instituted a number of financial and social reforms, which earned him the hostility of the aristocracy and even Marie Antoinette.

In 1781, he was forced to retire, but he was recalled in 1788 in an attempt to rescue France from imminent bankruptcy. His address to the Estates General (1789) included numerous plans for liberal but not radical political reform, calling for a limited constitutional monarchy like that of Great Britain. His dismissal by the King on July 11th increased the anti-aristocratic sentiments of the more radical reformers. Although he was recalled only days later to deal with the deficit of the new revolutionary government, he retired in September 1790 to Coppet, Switzerland, where he remained until his death in 1804. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Comte Hans Axel von Fersen |

| |

Born on September 4, 1755 in Stockholm, Comte Hans Axel von Fersen was a Swedish soldier and diplomat and the son of Count Fredrik Axel Fersen. In 1779, He entered the French service, was aide-de-camp of Comte de Rochambeau in the American Revolution, and later at the court of Versailles became a favorite of Marie Antoinette. Born on September 4, 1755 in Stockholm, Comte Hans Axel von Fersen was a Swedish soldier and diplomat and the son of Count Fredrik Axel Fersen. In 1779, He entered the French service, was aide-de-camp of Comte de Rochambeau in the American Revolution, and later at the court of Versailles became a favorite of Marie Antoinette.

They met on January 30, 1771, at a masked ball in Paris. Over the years and though they were never known to be alone, they talked to one another and sent private letters back and forth. After his return from the United States, she give him a memento, a small almanac on which she had embroidered the words: “Foi, Amour, esperance, trois, unis `a jamais”. In english, the phrase is simply: "Faith, love and hope, never go to United States. Axel had a special ring made for the Queen which was inscribed: “All leads me to thee”. Eventually, he was recalled to Sweden in 1784, but returned to Paris on the eve of the French Revolution.

In 1791, he assisted the Marquis de Bouillé plan the flight of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. He himself drove their coach outside the city limits of Paris. It was unfortunate that the King and Queen were arrested at Varennes and forced to return to Paris. Throughout his life, he remained the Queen's closest male confident and possibly plutonic lover to the end.

Fersen later held diplomatic posts at Vienna and Brussels. In 1801, he was made Marshal of Sweden by Gustavus IV, whom he accompanied to Germany in the Napoleonic Wars. After the Swedish revolution of 1809 that forced Gustavus IV to abdicate, Fersen was accused by popular rumor of reactionary intrigues and was killed by a mob in 1810 in Stockholm. |

|

| |

|

|

| Jacques Turgot |

| |

Jacques Turgot, the Baron de l'Aulne, was perhaps the leading economist of 18th century France. Although often lumped together with the Physiocrats, his contributions were quite distinct and advanced considerably upon Physiocratic theories. The physiocrats were a group of economists who believed that the wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land agriculture or land development. Jacques Turgot, the Baron de l'Aulne, was perhaps the leading economist of 18th century France. Although often lumped together with the Physiocrats, his contributions were quite distinct and advanced considerably upon Physiocratic theories. The physiocrats were a group of economists who believed that the wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land agriculture or land development.

Turgot can be said to have formed a distinct school of his own, counting the Abbé Morellet and the Marquis de Condorcet as close friends and disciples. More importantly, Turgot exercised a deep influence upon Adam Smith, who was living in France in the 1760s and was on intimate terms with Turgot. Smith was a Scottish moral philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. Many of the concepts and ideas in Smith's Wealth of Nations are drawn directly from Turgot.

Turgot was adamant about saving the finances of the decrepit Ancient Regime. He figured that if he could keep government spending in check and encourage private economic enterprise, tax revenues would rise and state finances would return to solvency. However, he believed that the old Colbertiste strategy of state-sponsored corporations and protectionist measures kept industry uncompetitive and unproductive. Inspired by Vincent de Gournay, Turgot intended to unleash the forces of competition and free markets. To do so, not only would he have to reverse Colbertiste economic policies, he would also have to dismantle the medieval institutions that kept the French economy in enslaved in old ideals.

By now, Turgot had successfully made enemies with practically every class of person in France, except the economists, who cheered him on. In the French court, his back was covered only by the king; however, when Turgot crossed Queen Marie Antoinette by refusing favors to her protégés, the die were cast. Turgot was dismissed in 1776. Before departing, Turgot presciently warned Louis XVI, "Do not forget, Sire, that it was feebleness that placed the head of Charles II on the block." Condorcet, then at the royal mint, attempted to resign in protest. Turgot was succeeded by Jacques Necker, who proceeded to reverse most of his edicts and policies. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Estates General |

| |

The French monarchy was more firmly fixed in power by the unfailing succession of the Capetian line to Louis XVI. In previous reigns and centuries past of France’s history, the Estates General never gained the right to make laws as the English Parliament did. During the Hundred Years' War, from 1337 to 1453, the Estates-General could frequently force the King to do as it wished by refusing him money to carry on the struggle, but it sometimes lost public respect by favoring civil strife or by allying itself with the English invaders.

In 1439, near the close of the war, the Estates General granted a land tax, the taille from which the nobles were exempted. Since there was no opposition when the King chose to consider such grants to be permanent, the King became independent. He had plenty of revenue, a standing army, dominated the clergy, and dispensed favors to the nobles. The King had little need of the Estates General.

For 174 years, beginning in 1614, the representatives of the three estates were not summoned to consider the affairs of the kingdom. In 1788, Louis XVI was forced to call this almost forgotten body together again due to the fact that the treasury was empty. When they met on May 5, 1789, the representatives of the third estate, equal in numbers to the other two, refused to vote according to the old method by which each estate cast one vote. They insisted on voting as individuals and declared themselves the National Assembly. On June 20, 1789, they took the famous “Tennis Court Oath” not to disperse until they had given France a constitution. This bold attitude showed clearly that a revolution was at hand.

The name "Estates General" was not uncommon in medieval Europe. In Spain, there were four estates, or classes, in the assembly. In The Netherlands, the name States General is still applied to the legislative body of that kingdom. It is composed of two houses, the upper house is elected by the Provincial Assemblies, and the lower house is chosen by the people. |

|

| |

|

|

| Affair of the Diamond Necklace |

| |

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace" scandal that took place at the court of King Louis XVI of France just before the French Revolution. An adventuress who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte duped Cardinal de Rohan, the grand almoner, who was out of favor with Queen Marie Antoinette, into believing that the Comtesse could regain the Queen's regard for him. The Affair of the Diamond Necklace" scandal that took place at the court of King Louis XVI of France just before the French Revolution. An adventuress who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte duped Cardinal de Rohan, the grand almoner, who was out of favor with Queen Marie Antoinette, into believing that the Comtesse could regain the Queen's regard for him.

The Comtesse and her accomplices then engineered a sham correspondence between the Cardinal and the Queen and even arranged an interview between him and a woman impersonating Marie Antoinette. On the grounds of la Petit Trianon, the meeting did occur. The perception was put in place that the Queen would now allow him her approval in the court of Versailles and that she too shared a special intimacy with him. Even though the meeting may have lasted for only a few moments, it was enough to be the catalyst that pressed the Cardinal to go into action on her behalf. Upon the success of the meeting, the Comtesse conveyed the wishes of the Queen to acquire a diamond necklace of enormous value and that she had chosen him as her confidential agent.

When Rohan obtained the necklace from the jewelers, he turned it over to the Comtesse; her husband took it to London, where it was broken up for sale through out Europe. The affair became public after Queen and her agent, Cardinal Rohan, failed to meet the payments to the jewelers. The Cardinal was arrested and tried by the Parliament; he was acquitted but lost his position in court and was exiled. Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was punished and imprisoned, but she escaped to London, where she wrote her highly questionable memoirs.

Alessandro Cagliostro, a medium who aided the assembly in fooling the Cardinal, at first suspected of complicity was acquitted. The Queen, noted for her extravagance and frivolity, was unjustly implicated in the affair. Her enemies hinted that she had schemed to ruin the Cardinal or that she had used her favor to obtain the necklace and then refused to pay. The scandal added greatly to her unpopularity at a critical time. Alessandro Cagliostro, a medium who aided the assembly in fooling the Cardinal, at first suspected of complicity was acquitted. The Queen, noted for her extravagance and frivolity, was unjustly implicated in the affair. Her enemies hinted that she had schemed to ruin the Cardinal or that she had used her favor to obtain the necklace and then refused to pay. The scandal added greatly to her unpopularity at a critical time.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Centuries ahead of her time, Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was a beguiling and unconventional woman who broke all the rules and masterminded an ingenious and perilous conspiracy that scandalously incriminated the rich and famous and may well have paved the way to the guillotine for Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI, ending 800 years of absolute Monarchy.

Centuries ahead of her time, Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte was a beguiling and unconventional woman who broke all the rules and masterminded an ingenious and perilous conspiracy that scandalously incriminated the rich and famous and may well have paved the way to the guillotine for Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI, ending 800 years of absolute Monarchy.  At the center of Jeanne's plan was a spectacular and outrageous piece of jewelry, a 2,800-carat, 647-diamond necklace. It was so costly that no Royal Court in Europe could afford to purchase it. France's royal jewelers had created the elaborate string of diamonds for the mistress of King Louis XV, Madame du Barry. However, before the piece was completed, the King died and his mistress was banished from Court. The jewelers then tried to sell the opulent necklace to Marie Antoinette, but when the Queen flatly refused their masterwork, they faced imminent bankruptcy. Desperate for a sale, they began to look for ways to approach the Queen in a more discreet manner.

At the center of Jeanne's plan was a spectacular and outrageous piece of jewelry, a 2,800-carat, 647-diamond necklace. It was so costly that no Royal Court in Europe could afford to purchase it. France's royal jewelers had created the elaborate string of diamonds for the mistress of King Louis XV, Madame du Barry. However, before the piece was completed, the King died and his mistress was banished from Court. The jewelers then tried to sell the opulent necklace to Marie Antoinette, but when the Queen flatly refused their masterwork, they faced imminent bankruptcy. Desperate for a sale, they began to look for ways to approach the Queen in a more discreet manner.  Though Marie Antoinette probably never heard any of this, the jewelers were told that the Queen agreed to their price. Rohan, to endear himself with the Queen, negotiated the purchase.

Though Marie Antoinette probably never heard any of this, the jewelers were told that the Queen agreed to their price. Rohan, to endear himself with the Queen, negotiated the purchase.  Cardinal de Louis Rene Edouard Rohan, the Prince de Rohan-Guemenee and Archbishop of Strassburg, a cadet of the great family of Rohan, which traced its origin to the kings of Brittany and was granted the precedence and rank of a foreign princely family by Louis XIV. He was born in Paris on the Septemeber 25, 1734. Members of the Rohan family had filled the office of Archbishop of Strassburg starting from 1704. It was an office, which made them Princes of the empire and the compeers, rather of the German Prince-Bishops than of the French ecclesiastics.

Cardinal de Louis Rene Edouard Rohan, the Prince de Rohan-Guemenee and Archbishop of Strassburg, a cadet of the great family of Rohan, which traced its origin to the kings of Brittany and was granted the precedence and rank of a foreign princely family by Louis XIV. He was born in Paris on the Septemeber 25, 1734. Members of the Rohan family had filled the office of Archbishop of Strassburg starting from 1704. It was an office, which made them Princes of the empire and the compeers, rather of the German Prince-Bishops than of the French ecclesiastics.

Jacques Necker, 1732-1804, Director of Finance under Louis XVI. Having gained a reputation as a financial writer, Necker was appointed France's Directory of the Royal Treasury (1776) and a year later Director General of the Finances. In addition to attempting to raise money for the American War of Independence, he instituted a number of financial and social reforms, which earned him the hostility of the aristocracy and even Marie Antoinette.

Jacques Necker, 1732-1804, Director of Finance under Louis XVI. Having gained a reputation as a financial writer, Necker was appointed France's Directory of the Royal Treasury (1776) and a year later Director General of the Finances. In addition to attempting to raise money for the American War of Independence, he instituted a number of financial and social reforms, which earned him the hostility of the aristocracy and even Marie Antoinette.  Born on September 4, 1755 in Stockholm, Comte Hans Axel von Fersen was a Swedish soldier and diplomat and the son of Count Fredrik Axel Fersen. In 1779, He entered the French service, was aide-de-camp of Comte de Rochambeau in the American Revolution, and later at the court of Versailles became a favorite of Marie Antoinette.

Born on September 4, 1755 in Stockholm, Comte Hans Axel von Fersen was a Swedish soldier and diplomat and the son of Count Fredrik Axel Fersen. In 1779, He entered the French service, was aide-de-camp of Comte de Rochambeau in the American Revolution, and later at the court of Versailles became a favorite of Marie Antoinette.

Jacques Turgot, the Baron de l'Aulne, was perhaps the leading economist of 18th century France. Although often lumped together with the Physiocrats, his contributions were quite distinct and advanced considerably upon Physiocratic theories. The physiocrats were a group of economists who believed that the wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land agriculture or land development.

Jacques Turgot, the Baron de l'Aulne, was perhaps the leading economist of 18th century France. Although often lumped together with the Physiocrats, his contributions were quite distinct and advanced considerably upon Physiocratic theories. The physiocrats were a group of economists who believed that the wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land agriculture or land development.

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace" scandal that took place at the court of King Louis XVI of France just before the French Revolution. An adventuress who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte duped Cardinal de Rohan, the grand almoner, who was out of favor with Queen Marie Antoinette, into believing that the Comtesse could regain the Queen's regard for him.

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace" scandal that took place at the court of King Louis XVI of France just before the French Revolution. An adventuress who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Valois-Motte duped Cardinal de Rohan, the grand almoner, who was out of favor with Queen Marie Antoinette, into believing that the Comtesse could regain the Queen's regard for him.  Alessandro Cagliostro, a medium who aided the assembly in fooling the Cardinal, at first suspected of complicity was acquitted. The Queen, noted for her extravagance and frivolity, was unjustly implicated in the affair. Her enemies hinted that she had schemed to ruin the Cardinal or that she had used her favor to obtain the necklace and then refused to pay. The scandal added greatly to her unpopularity at a critical time.

Alessandro Cagliostro, a medium who aided the assembly in fooling the Cardinal, at first suspected of complicity was acquitted. The Queen, noted for her extravagance and frivolity, was unjustly implicated in the affair. Her enemies hinted that she had schemed to ruin the Cardinal or that she had used her favor to obtain the necklace and then refused to pay. The scandal added greatly to her unpopularity at a critical time.